Introduction With the digitally networked world of today, streaming has remade content consumption beyond recognition.…

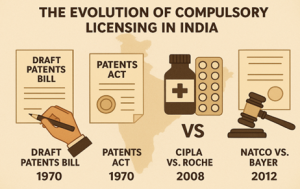

The Evolution of Compulsory Licensing in India: Post-COVID Trends

Abstract

Compulsory licensing under India’s Patents Act has always been a contested space, walking the tightrope between protecting pharmaceutical innovation and ensuring affordable public access to medicines. The debate took on renewed urgency during the COVID-19 pandemic, when shortages of drugs and vaccines brought the issue into sharp focus. Although Indian law contains strong provisions under Sections 84 and 92, the government refrained from issuing any compulsory licenses during the crisis, relying instead on voluntary licensing and administrative interventions. This decision sparked critical questions about the responsiveness of the framework in emergencies and India’s role as the “pharmacy of the developing world.” By revisiting the landmark Natco v. Bayer case and examining India’s cautious approach during the pandemic, this blog highlights the urgent need for reform—clearer definitions, streamlined procedures, and a more agile policy—to ensure that compulsory licensing remains a credible safeguard in future health crises.

Introduction

Compulsory licensing has always been seen as a safety valve in India’s patent law. It has been engineered to strike a balance between rewarding innovation and ensuring that essential medicines are not priced out of the reach of ordinary people. This question became especially important during the COVID-19 pandemic. With shortages of vaccines and drugs, and with prices going up, people started struggling with affordability and access and so the society as an institution and state as an enabler would ask as to whether patents should stand in the way of saving lives. India already had a system in place that allowed the endowment of compulsory licenses, but the government had a stark hesitation in using that economic tool thus leaving behind some demanding inquiries for the future.

The legal foundation is quite unambiguous. Under the Patents Act 1970, Section 84 allows any interested party to apply for a compulsory license three years after a patent has been granted. The grounds are fairly broad: if the invention is not meeting public needs, if the price is unreasonably high, or if the invention is not being “worked” in India. Alongside this, Section 92 lets the government act directly in times of emergency or extreme urgency. It means the law already provides a mechanism to override patents in situations like a pandemic. This is also a testament of India’s attempt to balance international commitments like the TRIPS agreement with its domestic priority to secure its people with a life of felicity.

Historical use and case studies

India actually illustrated the use of this tool in history of recognizing IP rights where In 2012, Natco Pharma applied for a license to produce a cheaper version of Bayer’s cancer drug Nexavar (Sorafenib). Bayer’s price was nearly ₹2.8 lakh per month, clearly unaffordable for most patients especially for patients in developing countries while Natco proposed to sell it at around ₹9,000. The Indian Patent Office agreed and issued the license venerated as a landmark order. This was a turning point, showing that India was willing to prioritise access over monopoly rights. But later applications, like for Dasatinib and Trastuzumab, were rejected. That showed compulsory licensing would be used only rarely, and not as a regular practice.

Covid 19 Pandemic and Compulsory licensing

When COVID-19 arrived, the conditions looked tailor-made for using Section 92. Hospitals struggled to get Remdesivir and other drugs, black markets popped up, and even vaccines were in short supply. Civil society groups, opposition leaders, and even some state governments like Punjab and Kerala pressed for compulsory licenses. The Supreme court also asked the government to think about it. At the same time, India and South Africa pushed for a TRIPS waiver at the World Trade Organization, asking for a temporary suspension of IP rights on COVID-related medicines. The official proposal, filed by World Trade Organization, gained wide support from developing countries but ran into resistance from richer nations. Eventually, the WTO agreed only to a narrow compromise, limited to vaccines, which many critics said was far too little and too late.

The way forward

This cautious approach leaves us with a few clear lessons. First, the system is not agile enough in emergencies. Even though the law permits it, the process is still slow, and delays during a health crisis can be deadly. Second, there is the issue of balance. On one side, pharma companies warn that compulsory licensing discourages research and innovation. On the other, refusing to use it in an unprecedented pandemic looked like putting patents ahead of patients. A middle path may be to use CL only for genuine emergencies but to act quickly when those emergencies arise. Third, the episode reinforced India’s role as the “pharmacy of the developing world.” India not only supplies its own people but also exports affordable generics across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Its stance on compulsory licensing therefore has ripple effects well beyond its borders. A transparent and credible policy here would also strengthen India’s global standing. Finally, there is a need for reform. Vague terms like “reasonably affordable” should be defined more clearly, and the government could consider a fast-track CL mechanism for health emergencies.

In the end, compulsory licensing in India is still a rarely used safeguard. The Natco v. Bayer order remains the one famous case, and the pandemic showed hesitation to use it when the stakes were highest. Looking forward, India has to ensure that compulsory licensing is neither ignored nor overused. It should be seen as a public health safety valve — not an attack on innovation, but a guarantee that, in times of crisis, access to medicine is never compromised. With a few targeted reforms, India can keep leading on affordable healthcare while respecting the global innovation ecosystem.

Author: Ananya Purohit, in case of any queries please contact/write back to us via email to [email protected] or at IIPRD.

References

- The Patents Act, No. 39 of 1970, §§ 84, 92, India Code (1970), available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/1795.

- Natco Pharma Ltd. v. Bayer Corp., Compulsory Licence Order (Controller of Patents, Mar. 9, 2012), available at https://www.globalhealthrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Natco-v-Bayer.pdf.(Global Health Rights)

- In re Distribution of Essential Supplies and Services During Pandemic, Writ Petition (Civil) No. 539 of 2021 (Sup. Ct. India), available at https://images.assettype.com/barandbench/2021-05/3e654bd3-8e3e-4641-ba9e-3525c111f6c7/IN_RE_DISTRIBUTION_OF_ESSENTIAL_SUPPLIES_AND_SERVICES.pdf.(Assettype)

- World Trade Org., Waiver from Certain Provisions of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment and Treatment of COVID-19, WTO Doc. IP/C/W/669 (Oct. 2, 2020), available at https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/IP/C/W669.pdf&Open=True.

- Press Release, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers, Govt. of India, Allocation of Remdesivir (Apr. 21, 2021), available at https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1713151.